May is Asian Pacific American Heritage Month, a time to pay tribute to the generations of Asian and Pacific Islanders who have enriched America’s history and are instrumental in its future success. We profile Soo Lee of HR, Venkat Srinivasan of ESDR, and Christine Naca of JGI.

Soo Lee, Compensation Manager, Human Resources

Soo Lee has seen a lot of changes in the Bay Area since her elementary school days, when she was placed in an English as a Second Language (ESL) classroom simply because she was Korean-American. Lee was born in the U.S. and had spoken English her entire life. Her parents emigrated from Seoul, South Korea, when her mom was seven months pregnant with her so that her father could attend graduate school in the U.S.

Soo Lee has seen a lot of changes in the Bay Area since her elementary school days, when she was placed in an English as a Second Language (ESL) classroom simply because she was Korean-American. Lee was born in the U.S. and had spoken English her entire life. Her parents emigrated from Seoul, South Korea, when her mom was seven months pregnant with her so that her father could attend graduate school in the U.S.

At the time, Lee says she didn’t think much of the ESL classes at her Pleasant Hill, California, elementary school, except that it was nice to be taken out of cursive lessons to easily identify items on flashcards. Now she thinks back to how all the Asian-American kids in her elementary school were automatically placed in ESL and realized how bizarre it was.

“In elementary school, I would say, ‘I’m from Korea,’ and people would say, ‘where’s that?’” she recalls. “The Bay Area has become so much more culturally aware since then.”

Lee’s husband is also Korean-American, and they’re raising their two kids in Orinda, where she says they see cultural awareness celebrated in their kids’ schools. “It’s a different world for our kids now,” she says.

Growing up, Lee says her link to her own cultural heritage was strong—her parents often spoke Korean to her, they celebrated Korean holidays, and attended a Korean church. “A lot of my friends, even now, are from the Korean church that we used to go to as kids,” she says.

Lee isn’t sure that her kids, as second-generation Korean-Americans, will feel as strong a link as she did. But she and her husband are keeping some Korean traditions alive, such as the “Dol” for a baby’s first birthday. Lee explains that the tradition of throwing a huge party and taking part in a traditional ceremony when a baby turns one stems from the fact that babies didn’t always make it to their first birthday long ago. It’s been a strong Korean cultural tradition ever since to celebrate that milestone.

Lee is also happy that her kids are simply getting a chance to be exposed to a wide variety of cultures. “Our nanny, for example, is from Peru, and she’s teaching our kids Spanish,” she says. “I just love the Bay Area for its cultural diversity; I’m so glad to be raising my kids here.”

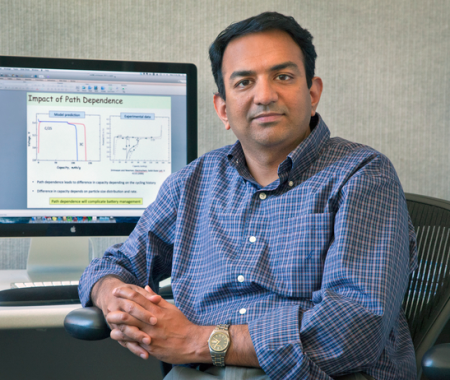

Venkat Srinivasan, Staff Scientist, Energy Storage and Distributed Resources Division

When Venkat Srinivasan, a Staff Scientist in the Energy Storage and Distributed Resources Division, came to the U.S. for graduate school in 1995, he didn’t really have a “grand vision” for his future, but he knew that his home country of India did not offer many opportunities for someone interested in scientific research. Most of his peers who stayed in India were going into high tech, while his college friends with similar scientific interests all headed off to the U.S. and were encouraging him to join them.

When Venkat Srinivasan, a Staff Scientist in the Energy Storage and Distributed Resources Division, came to the U.S. for graduate school in 1995, he didn’t really have a “grand vision” for his future, but he knew that his home country of India did not offer many opportunities for someone interested in scientific research. Most of his peers who stayed in India were going into high tech, while his college friends with similar scientific interests all headed off to the U.S. and were encouraging him to join them.

“Indians have always come to the U.S. for education, but when I finished my undergrad it seemed like that trend was increasing,” says Srinivasan. “And the sense was that you wouldn’t really want to be in the sciences in India; you’d want to go to America for that.”

Srinivasan studied electrochemical engineering at the University of South Carolina, where he says he thrived in an educational environment that valued curiosity. He spent most of his waking hours in the lab simply because he wanted to. “The United States was fantastic for me because the educational system was more about problem-solving,” he says. “I think for people who come from such a different system based on book learning, it’s really eye-opening.”

In the mid-1990s hybrid cars started taking off, and it was then that all the fun and interesting research that Srinivasan had been involved in took on a more real-world application. When Srinivasan finished grad school, he knew he wanted to go into research, and he knew he wanted to work with John Newman at UC Berkeley, whom he (and many others) refers to as “the godfather of electrochemical engineering.”

After one postdoc stint at Penn State, Srinivasan got his wish and landed a position at Berkeley with Newman. “All my Indian friends who’d moved here were in computers, all working for startups in Silicon Valley, and all millionaires on paper,” says Srinivasan.

“It was the turn of the century, at the height of the tech boom, and it was hard to be a poor graduate student working on batteries.”

After he finished his postdoc, Newman offered Srinivasan an opportunity to stay at Berkeley Lab, where he’s now been for 10 years. “Berkeley is an institution in the world of electrochemistry,” says Srinivasan. “Even back in India I knew that Berkeley had the deepest history in the field of electro-engineering, and I knew I wanted to be a part of that.”

Growing up, Srinivasan’s parents placed great value on education, choosing to eventually settle in Chennai partly because the city had excellent schools. He was always encouraged to pursue his academic ambitions, and he hopes to pass that along to his own child. Srinivasan and his wife both still have lots of family in India; they go back frequently to visit, and have taken their 2.5-year-old son to meet his extended family. They both speak their languages, Tamil and Hindi, with their young son and love to cook traditional Indian food at home.

Srinivasan observes that there are actually a lot of Indians moving back to India these days because the country’s economy is booming right now. Like many immigrants, he is not immune to the push-pull of his homeland. “India has changed so dramatically since I left in terms of its economy and peoples’ attitudes,” he says. “In some ways I regret not being there to see the shift.”

Christine Naca, Industrial Engineer, Joint Genome Institute

The core values that drove her parents to emigrate from the Philippines to the U.S. before she was born are the same ones that Joint Genome Institute (JGI) engineer Christine Naca now credits for her own achievements — namely, hard work and a good education. Naca says her parents left their home country to build a better life for their family in the 1970s, believing that working hard would lead to wider opportunities in the U.S. and that their children would benefit from the educational system here.

The core values that drove her parents to emigrate from the Philippines to the U.S. before she was born are the same ones that Joint Genome Institute (JGI) engineer Christine Naca now credits for her own achievements — namely, hard work and a good education. Naca says her parents left their home country to build a better life for their family in the 1970s, believing that working hard would lead to wider opportunities in the U.S. and that their children would benefit from the educational system here.

Though Naca now recalls that she was one of just a few minority students in her suburban Bay Area elementary school, as a child she was largely unaware of being “different” in any way. It was only when she travelled to the Philippines for the first time at age 16 that she fully realized what life was like in her parents’ home country, and what a different life she led in the U.S.

“The experience of being in a developing country, especially just a few years after the huge Mount Pinatubo volcanic eruption, was intense,” says Naca, as she describes driving from the airport past mothers and children begging by the side of dirt roads. “It really made me think about how it would be to live like that, how my life could have been.”

That perspective has informed her choices and her personal ambition ever since. In college at San Jose State, she joined the Minority Alliance program, which not only gave her academic opportunities but allowed her to connect with her peers and offer assistance to other minority students. She joined a Filipino heritage club in college as well. After earning a degree in industrial and systems engineering, Naca has built a successful career and started her own family.

Since 2003 she’s been at the JGI, where she’s now a project manager overseeing the new technology implementation program. She’s used her expertise in workflow efficiency—reducing cost, increasing efficiency, and minimizing safety risks—to lead a JGI team to three ergonomics design competition wins since 2007. Naca volunteers as the lead of JGI’s safety, health, wellness, and sustainability (SWELL) team.

“You work hard to get where you want to be—that’s the culture in the Philippines and an ethic that my parents instilled in me,” Naca says.

Naca has travelled to the Philippines twice more since her teenage years, once with one of her two children. She and her husband, who is also Filipino-American, both still have extended family living there. Her father travels back to the Philippines frequently and Naca sends books and children’s toys and clothing with him to distribute.

“I feel very fortunate to have the opportunities I do; though I’ve never lived the life that my extended family has, I am aware of it,” she says. “By living in America, I’ve been offered opportunities to work hard and take advantage of opportunities that I just wouldn’t have had in the Philippines.”

Naca and her husband hope to pass these values along to their own children, in addition to teaching them about their cultural heritage through food, family, and language. Though neither of them are fluent in the dialects of their respective Filipino provinces, Naca and her husband have asked their parents to teach as much of the language to their children as possible. “I feel lucky to be raising my children in the Bay Area, where there’s so much opportunity and diversity, and I can expose them to so much,” Naca says.

-Keri Troutman